SET is a classic pattern-matching card game that's been around since the 1970s, but really took off in the 90s. It hits all the right marks for a great game casual game; easy to learn, works for any number of players, you can play for 5 minutes or for hours, little equipment required, and it's always competitive.

Here's how it works: using a special set of 81 cards, deal 12 at random, face up. Each card is has a unique combination of 4 attributes: Color, shape, fill, and number, each of which has three different possible values. So after dealing you get something like this:

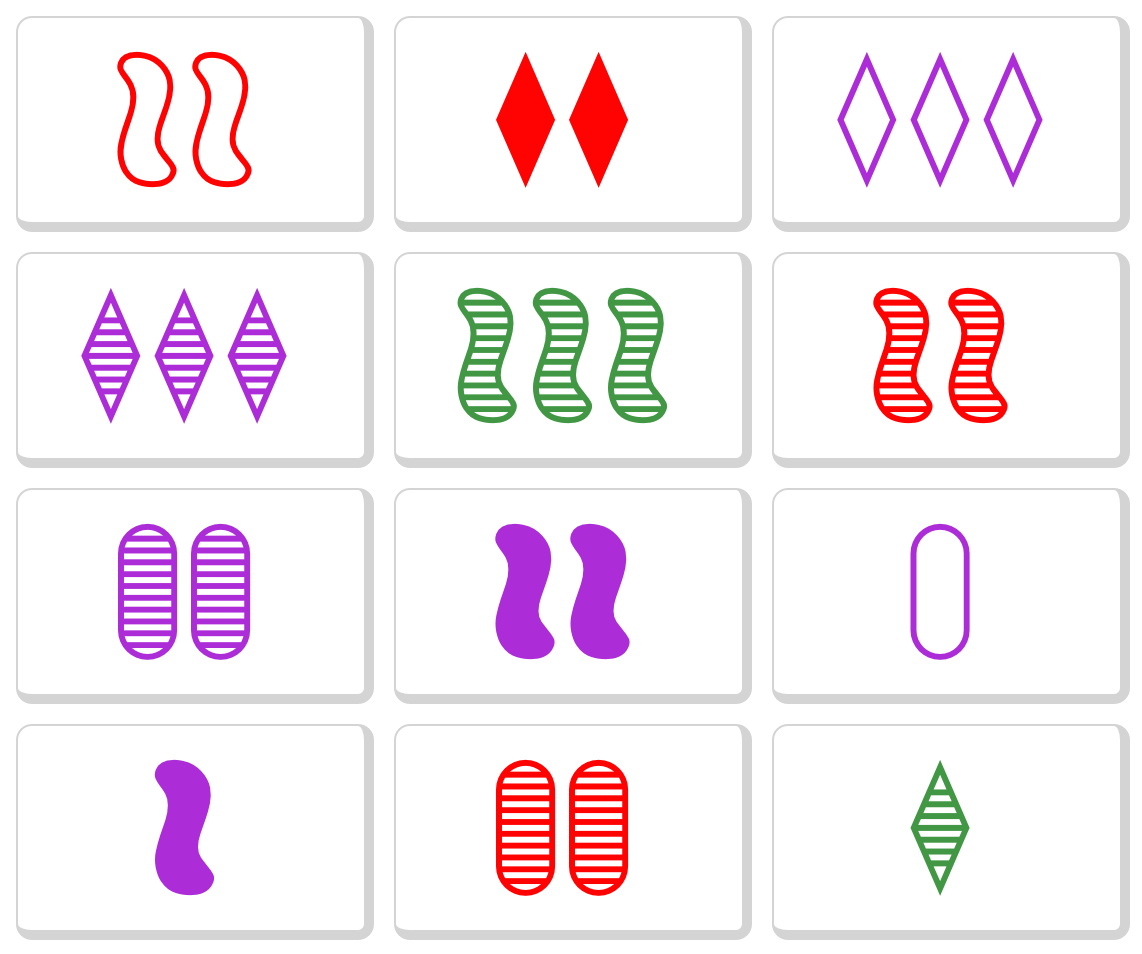

Players shout "set!" when they identify a "valid set". A valid set consists of exactly three cards, for which each of the four attributes are either all the same or all different. So here's a valid set from the deal above:

You can see that, for each of the four attributes, all the cards either completely match or are completely different.

| Attribute | Card 1 | Card 2 | Card 3 | Set |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 3 | 2 | 1 | Different |

| Fill | Lined | Open | Solid | Different |

| Color | Green | Red | Purple | Different |

| Shape | Squiggle | Squiggle | Squiggle | Same |

If you were to change any attribute on any of the cards in the set, you'd have some attribute for which 2 cards matched, and the third different, thus making it an invalid set. When someone finds a set, you remove it, and deal three new cards in their place. You go through the entire deck until there are <=12 cards left, with no more sets. Whoever claimed the most sets wins.

The rules are very simple, but the fun comes from staring at the cards as they are dealt, frantically trying to find sets before you opponent. If my brain had a cooling fan, it would immediately turn on as my cognitive load instantly maxes out.

To understand a little better what I was looking for (and to fiddle around with Python, which is always fun), I sought to determine how many sets are likely to be in the first 12 dealt cards. Here's the code to generate a deck of SET cards, and detect whether a set (or multiple sets) are present. There are a few "unnecessary" methods in the below because (spoilers!) we are going to simulate a lot of Set games later and this turned out to make quite a difference.

> Run the code

You can run and edit all of the code in this blog post right from your browser.

from itertools import combinations

import random

attributes = ['number', 'fill', 'color', 'shape']

def make_cards():

# 1, 2, 3, open, shaded, filled, purple, green, red, diamond, squiggle, oval

return ['{}{}{}{}'.format(n, f, c, s)

for n in '123' for f in 'osf' for c in 'pgr' for s in 'dso']

def _valid(elems):

# Members of elems are all the same, or all different

return len(set(elems)) != 2

def _is_set(a,b,c):

return all([

_valid([a[x], b[x], c[x]])

for x in range(4)]) # 4 is the number of distinct attributes

def find_sets(cards):

return [c for c in combinations(cards, 3) if _is_set(*c)]

def find_set(cards):

# The same as above, but bails as soon as it finds a set. Again, performance thing.

for c in combinations(cards, 3):

if _is_set(*c):

return c

def sets_exist(cards):

# Perf optimization: 21+ cards guarantee a set

# via https://mathscinet.ams.org/mathscinet-getitem?mr=2031694

return len(cards) > 20 or bool(find_set(cards))

def test():

assert len(make_cards()) == 81

assert len(find_sets(make_cards())) == 1080

cards = '2ors,2srd,3opd,3fpd,3fgs,2frs,2fpo,2sps,1opo,1sps,2fro,1fgd'.split(',')

assert sets_exist(cards)

assert not sets_exist(cards[:8])

assert len(find_set(cards)) == 3

assert len(find_sets(cards)) == 6

test()

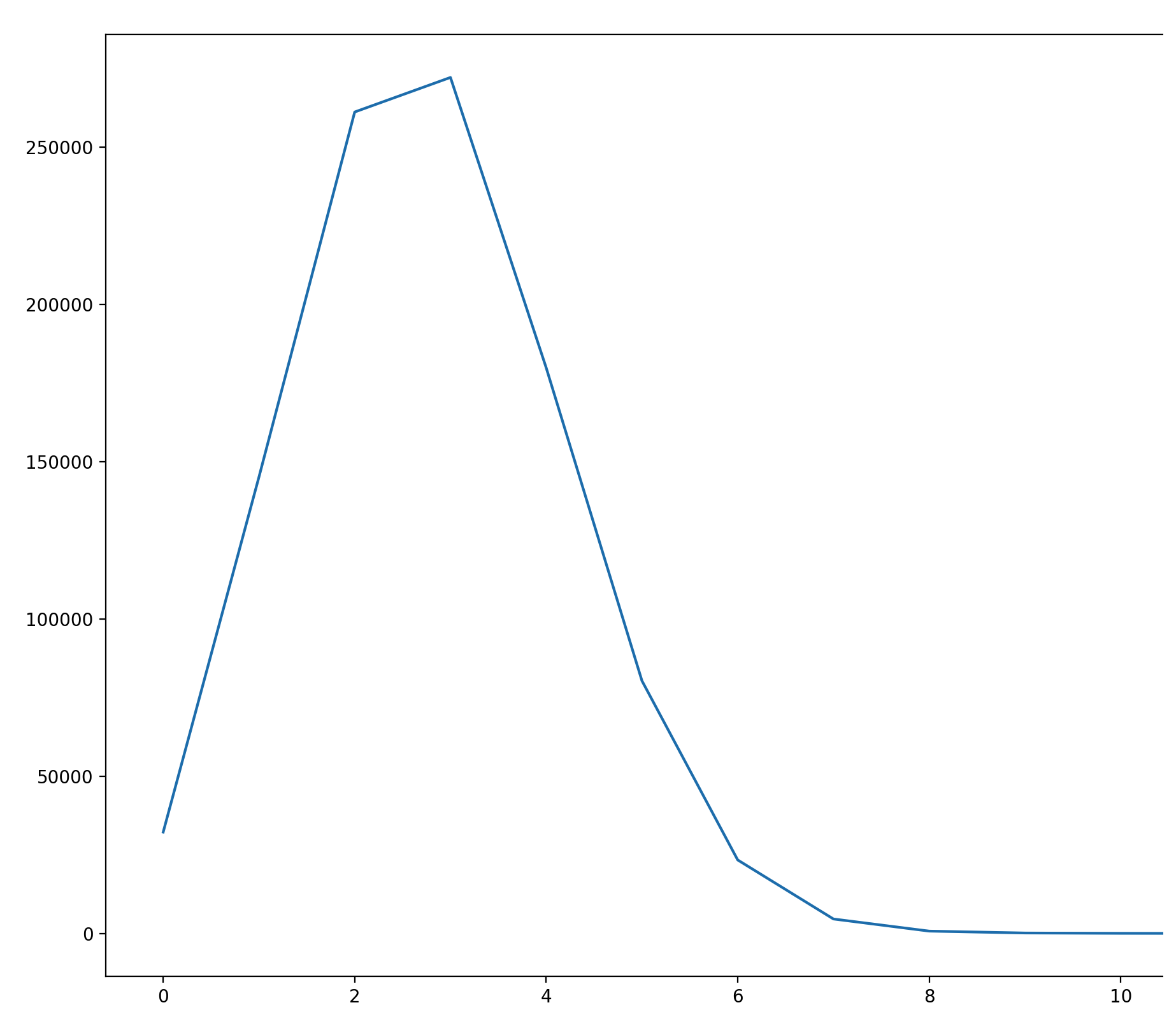

We can now empirically determine some facts about the game. I simulated one million 12-card deals (from a fresh deck each time) to see how many sets appear in the initial draw of a game.

sets = [len(find_sets(random.sample(make_cards(), 12)))

for _ in range(1000000)]

print("Avg sets:", sum(sets) / len(sets))

print("Min sets:", min(sets))

print("Max sets:", max(sets))

for x in range(min(sets), max(sets)+1):

print("{} sets {:.4%} of the time ({} of {})".format(x, sets.count(x) / len(sets), sets.count(x), len(sets)))

Results:

Avg sets: 2.78542

Min sets: 0

Max sets: 12

0 sets 3.2228% of the time (32228 of 1000000)

1 sets 14.5164% of the time (145164 of 1000000)

2 sets 26.1262% of the time (261262 of 1000000)

3 sets 27.2253% of the time (272253 of 1000000)

4 sets 17.9905% of the time (179905 of 1000000)

5 sets 8.0349% of the time (80349 of 1000000)

6 sets 2.3360% of the time (23360 of 1000000)

7 sets 0.4585% of the time (4585 of 1000000)

8 sets 0.0731% of the time (731 of 1000000)

9 sets 0.0129% of the time (129 of 1000000)

10 sets 0.0031% of the time (31 of 1000000)

11 sets 0.0002% of the time (2 of 1000000)

12 sets 0.0001% of the time (1 of 1000000)

To build intuition, we can chart it:

%matplotlib notebook

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot([x for x in range(min(sets), max(sets)+1)],

[sets.count(x) for x in range(min(sets), max(sets)+1)])

plt.show()

Neat! The > 10 set case turns out to be quite rare, even though in theory (see page 18) 14 sets can exist in a 12-card deal.

Next up, let's play a full game. The code below accomplishes that.

def run_game():

deck = make_cards()

random.shuffle(deck)

table = deck[:12]

deck = deck[12:]

state_log = []

while sets_exist(table + deck):

s = find_set(table) or []

state_log.append({'table': len(table), 'deck': len(deck), 'set': bool(len(s))})

table = [c for c in table if c not in s]

# Don't put more cards down if a set was drawn from a 15+ card table

if not(s and len(table) >= 12):

table += deck[:3]

deck = deck[3:]

return state_log

result = run_game()

for step in result:

print("{table} cards on the table. {deck} cards in the deck. Set: {set}".format(**step))

Game output:

12 cards on the table. 69 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 66 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 63 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 60 cards in the deck. Set: False

15 cards on the table. 57 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 57 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 54 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 51 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 48 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 45 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 42 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 39 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 36 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 33 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 30 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 27 cards in the deck. Set: False

15 cards on the table. 24 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 24 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 21 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 18 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 15 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 12 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 9 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 6 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 3 cards in the deck. Set: True

12 cards on the table. 0 cards in the deck. Set: True

9 cards on the table. 0 cards in the deck. Set: True

Up next, let's see how many times in an average game there are no sets in 12 cards, and 15 cards are required (Or 18! Or, in theory at least, 21!). We simulate 10,000 games and keep track of how many times there are different cards on the table (as well as how many cards are on the table at the end game):

from collections import Counter

fifteens, eighteens, twentyones, final_cards_on_table = [], [], [], []

for _ in range (10000):

result = run_game()

table = [r['table'] for r in result]

# Remove a final 3 cards if a final set has been found

final = table[-1]-3 if result[-1]['set'] else table[-1]

final_cards_on_table.append(final)

fifteens.append(table.count(15))

eighteens.append(table.count(18))

twentyones.append(table.count(21))

print("Final cards on table:\n{}".format(Counter(final_cards_on_table)))

print("Fifteens: {} times in {} games.".format(sum(fifteens), sum([x>0 for x in fifteens])))

print("Eighteens: {} times in {} games.".format(sum(eighteens), sum([x>0 for x in eighteens])))

print("Twenty Ones: {} times in {} games.".format(sum(twentyones), sum([x>0 for x in twentyones])))

Let's see:

Final cards on table:

Counter({6: 4853, 9: 4838, 12: 172, 0: 136, 15: 1})

Fifteens: 14327 times in 6696 games.

Eighteens: 144 times in 139 games.

Twenty Ones: 0 times in 0 games.

It appears we'll get a "15" on the table at some point about 2/3rds of the time, and 18 cards only 1.4% of the time. It's also interesting that the vast majority (97%!) of games end with either 6 or 9 cards left on the table, and it's about evenly split between those two outcomes. This surprised me; it's not intuitive to me that the final 12 cards would have about the same odds of containing a set as a final 9 cards. Said differently, given a final 12 cards, it's even odds that it contains exactly 1 set or exactly 2 sets (non-intersecting). You'll also notice that "3" does not appear as endgame scenario. This makes sense - if 78 of 81 cards in the deck have been made into a set, the last three cards must also be a set.

Lastly, I wondered how useful it would be to continue looking for a set after your opponent calls "Set", but before they have collected the cards from the 12 on the table. We generate 100,000 first draws, find all sets, pick one at random, remove it, and then check if another set exists in the remaining 9 cards.

deck = make_cards()

random.shuffle(deck)

table = deck[:12]

deck = deck[12:]

sets_in_first = []

sets_in_remainder = []

for x in range(100000):

deck = make_cards()

random.shuffle(deck)

table = deck[:12]

s = find_sets(table)

if s:

sets_in_first.append(len(s))

picked_s = random.choice(s)

table = [c for c in table if c not in picked_s]

s = find_sets(table)

if s:

sets_in_remainder.append(len(s))

print("Odds a set is still around after the first set is taken: {:.2%}".format(

sum(sets_in_remainder) / sum(sets_in_first)

))

And the result:

Odds a set is still around after the first set is taken: 28.28%

It appears that if you can spot a set just after your opponent calls "set", there is a ~28% chance that your late-spotted set will still be there after your opponent has collected their three cards (at least, for the very first deal of the game).

This is really interesting. The odds that two non-intersecting sets exist in the first twelve cards is about half the odds that two non-intersecting sets exist in the final 12 cards. That means that, not only should you continue looking for sets as your opponent is collecting cards and dealing new ones, but that that strategy becomes more powerful later in the game (presumably linearly, though I haven't verified).

For more SET fun and other analyses, Peter Norvig has (of course!) done that a great job.

This code was fun to write, and perhaps you can do some more exploration from here!