Want to get started using PGP on your Mac, but confused by the morass of professor-doctor style sites with seemingly out-of-date software and plugins? Have no fear! I'll have you up and running in minutes with this handy guide. You'll learn how to use public key servers and how to encrypt and send and receive and decrypt emails, and how to sign and verify messages using GPG. By the time you're done, you might actually find the GPG manual pages for simple tasks illuminating instead of totally incoherent.

Really explaining how public key encryption works or why you'd want to use it is not the goal of this post by a long shot - this is just a simple block-and-tackle tutorial on how to use the stuff. If you want an easy-to-read, non-technical intro to asymmetric cryptography, go read the first section of chapter 10 of Little Brother by Cory Doctorow. But with that said, I'd be remiss if I didn't at least provide...

Part 0 - A Two-Sentence Introduction to Public Key Encryption

Everyone who wants to communicate securely generates their own pair of keys, one of which they publicize, and one of which they keep private. To send someone a secure message, just encrypt your message with the recipient's public key, and that person (and only that person) will be able to decrypt it using their private key.

Got it?

Part 1 - A Quick Disambiguation of PGP, OpenPGP, and GPG

PGP stands for Pretty Good Privacy and is a piece of software that implements the OpenPGP public key (or asymmetric) encryption standard. The PGP implementation is owned by Symantec. GPG is another, free, implementation of OpenPGP that stands for Gnu Privacy Guard. GPG is very common on *nix systems and it's what we'll use here. So basically GPG and PGP are functionally equivalent.

Part 2 - Installing Stuff

We're going to use a Thunderbird (which is a great email client by Mozilla) extension called Enigmail to send and receive GPG emails. Let's get installing!

- Get Thunderbird and hook it up to an email account you use. Thunderbird is pretty great, and works well with Gmail (you only need to do the super short instructions in the "configuring your gmail" section - it's that easy). Ok done? Good.

- Now we need to install GPG. For OS X, you'll want GPG Suite. It's super easy to install, and will walk you through creating your first GPG key pair just after installation. It will default to an RSA key of 2048 bits, but I'd recommend using 4096. It's quite a bit more secure and really doesn't have any downsides - it's a bit more computationally expensive, but that doesn't matter unless you're using the key for something like SSL. We're just encrypting emails here.

- Finally, install Enigmail. This is a Thunderbird extension that provides simple integration with GPG so you don't have to muck about with a bunch of command line tools just to deal with sending and receiving email. There are a few configuration options - odds are, unless you are a character in Cryptonomicon, you don't want to encrypt or sign your messages by default. The official homepage of Engimail makes it look a little long in the tooth but it works great with the latest version of Thunderbird.

Part 3 - Using Key Servers

Now that you have a key pair created, you need to share it with the world - so that anyone who wants to communicate with you securely can encrypt messages to you with your public key. There are a number of organizations that maintain public keyservers to do just this. Key servers are just searchable directories of public keys. I use the MIT's because Phil Zimmerman, the inventor of PGP, is an MIT guy, and the server has been around a heck of a long time.

Go ahead and search for me. That's my key!

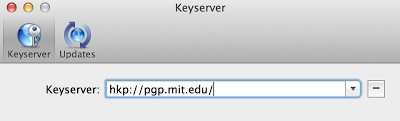

If you click on the key, you'll actually see the long block of gibberish that is my public RSA key. But you don't even have to interact with that - the GPG Suite makes it super easy to publish and install keys public keys. In the GPG Keychain Access tool (under Applications on your Mac), go to Apple > Preferences and point to the MIT key server:

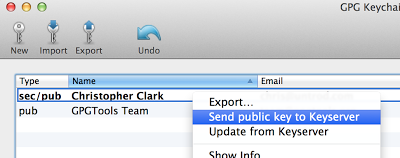

Now you can publish your public key to the server by right-clicking your key and hitting "Send public key to Keyserver":

Now go search for your email on MIT's servers and you can find your public key! Not only that, MIT's key server will propagate your key to other keyservers all around the world.

Installing keys is just as easy. You can install mine by going to Key > Retrieve From Keyserver and putting in my key ID from MIT's server (0x6f0eff6b2e0593ad). That's me! And now the world can find your public key just as easily.

Part 4 - Sending & Receiving Encrypted Messages

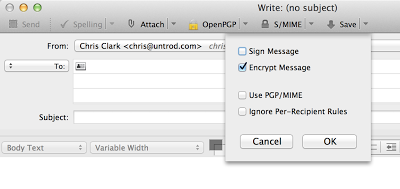

With Engimail installed, this is really pretty easy. Open Thunderbird and compose a new message. You'll see the OpenPGP drop down menu at the top, and you can elect to encrypt the message.

When you go to send the message, you'll of course have to select the public key with which to encrypt the message. Enigmail will detect the key automatically if you have a key with a matching email address on file with your GPG Keychain already, but if not you'll have to select one (or, more likely, go retrieve and install the correct one from a keyserver).

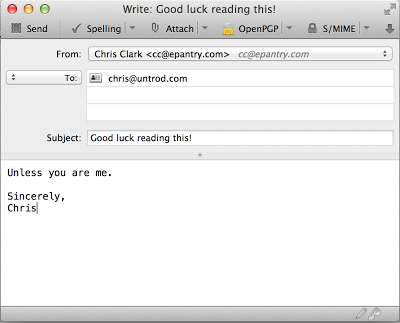

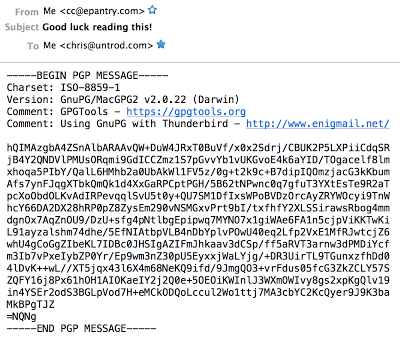

So if you write me a message like this:

And choose to encrypt it with my private key, here is the email that actually gets sent (note that the subject line is NOT encrypted):

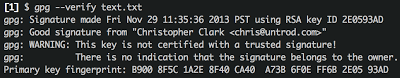

And if I open it in Thunderbird, Engimail detects the encryption, prompts for my password, decrypts it, and lets me know that it's decrypted a message:

Couldn't be easier! The harder thing is actually finding someone who also knows how to send and receive encrypted emails. Hah hah.

Part 5 - Signing & Verifying Emails

Besides keeping communication private, public key cryptography has another superpower - identify verification. The properties of the private/public key pairs means that, not only can someone else use your public key to encrypt a message that is only decryptable by you, but you can encrypt a message using your private key that can only be decrypted by your public key. Now, you may be asking yourself "why is that useful? Why bother encrypting a message that anyone can then read?". Well, if the message can be decrypted using your public key, then it must have been signed using your private key - which means you must have sent the message! Thus we can exploit public key cryptography for identity verification, as well as secret-message sending.

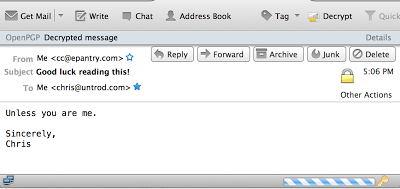

A signed message looks like this:

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNED MESSAGE----- Hash: SHA512 Really! -----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE----- Version: GnuPG/MacGPG2 v2.0.22 (Darwin) Comment: GPGTools - https://gpgtools.org Comment: Using GnuPG with Thunderbird - http://www.enigmail.net/ iQIcBAEBCgAGBQJSmOyIAAoJEG8O/2suBZOtmSUQAMSEbn13rjey0L9trG/Qc3eI DEvbnl1Vkx+37d7o8GVtwqmD5uwfh2RphyRq/l1ML3fz00pFzmMH7mfNib6BVZ9U nMXkN+r3x2VUUCNcYbn6i3lXWkxNwYiUIiUQpgwj9DKKv3n7ujNxC/u/1d+dcVK4 hlrf1oHCMMPIcqyQKDRKkPNOB9LGm1Y1KlKFKA6C/ElEAn/48kJKlCKZA55VJSk2 TuxutrduaPOkPjuY9zBGHWlcfF5d1CtZaQALPxjcBbS0z9mSW4vqJRO4kRUY7SAV jWFBfmPKNVPcZQTqvPd6CfqyQqmgCnl1fIHThHviWAMbX3GdGjsscRSzC3DiJRgZ cMcXLqjlqWYaml/6Iq8V8+Azk6Ph2ORxZOsKDiOAz+VwZRQwlyjMu9SSkA/VABEY dN7OrNZZwTwz2A1/QH/SHNvRVAB3kLRpzJTaLJsuFBeh5aycjjbhETHtYccYsxDf rmuGnnfxBrglkbBaYExxzKutaE/yVeFLSegO9clxa2biSk31X51kOjS/2Vy8UQgd iVRNQb/3ArfjOFiQvXIylGkJS0aiVmJXrkEOyiSzy5h0JGxpa2T4JWZ9VyrpGzLx 8PJUPPcYUGcfTEcB0dRvBC7/GpTn/ChEcMBfrPAqI+srsPG0CIBp+aIDAQEsSH61 tWVnIgeDuHCOFrNrB3bK =SYaF -----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

Under the hood, the signature was generated by hashing the message contents (in this case you can see Enigmail inserted the hashing algorithm it used - SHA512), then using the sender's private key to encrypt the hash along with a timestamp. The recipient can then verify the message by decrypting the signature blog, re-hashing the contents, and comparing. Not only is the sender's identity verified, but so are the message contents and the sending time. Cool!

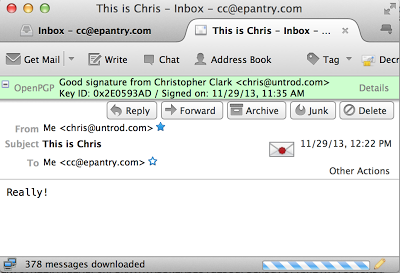

Sending and receiving signed messages through Engimail is just as easy as sending and receiving encrypted messages - just select the option when sending, and Enigmail handles everything for you. Signed messages are automatically verified. Here's what the above message looks like when viewed in Engimail:

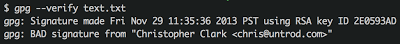

Sometimes you might want to verify blocks of text (or an email you received through a client other than Thunderbird). That's really simple with GPG as well, though you'll have to go to the command line. To try it out for yourself, save the above signed message as test.txt and then run the following from a terminal window:

Ta-da! Piece of cake.

A Quick Digression About Trusted Signatures

You'll see an ominous WARNING in the gpg output above, letting you know that this is not a trusted signature. This simply means that you have not indicated that you trust the source of the public key you used to decrypt the message. For instance, what if I am not Chris Clark at all? But some nefarious impersonator who has broken into Chris' blog and provided a public key in this post that is not Chris' at all? What then?? Who can we trust?

Turns out this is actually a pretty hard problem to solve. The PGP community has a concept called the web of trust, which you can read about on your own. Another approach is key signing parties. Ultimately you will need to make the trust determination on your own. You can then set your trust level for each public key in the GPG Keychain tool. By default all keys except your own are "undefined", and this warning won't go away until you've indicated you have "ultimate" trust in the key.

Back to verification

For kicks, try modifying the message slightly - replace my "Really!" with "Really." and re-run the verification (also note that I've now set my own key back to "Ultimate" trust so the warning is gone):

And that's it! You know how to use the GPG tool to communicate securely. There are all sorts of intricacies and details that are loads of fun to learn about, and you should now have a bit of a foundation to go exploring. Maybe those manual pages aren't so cryptic now after all. Good luck, and leave a comment if you'd like to exchange some encrypted emails with yours truly. You know where to find me.